The distance between bus stops may not appear to be a particularly well discussed issue in the industry.

However, a data expert who has acted as a consultant for local authorities on transport issues has claimed the UK has too many of them compared to other countries and that it is harming public transport as a service, having a negative knock-on effect on the productivity of our cities.

Tom Forth, Head of Data at Open Innovations, helped Transport for West Midlands (TfWM) identify 59 stops that could be removed to boost the bus network as part of a controversial trial carried out in 2017.

He believes Birmingham is not atypical in the UK and that other cities could similarly benefit from making passengers walk further on occasions in order to speed up bus services.

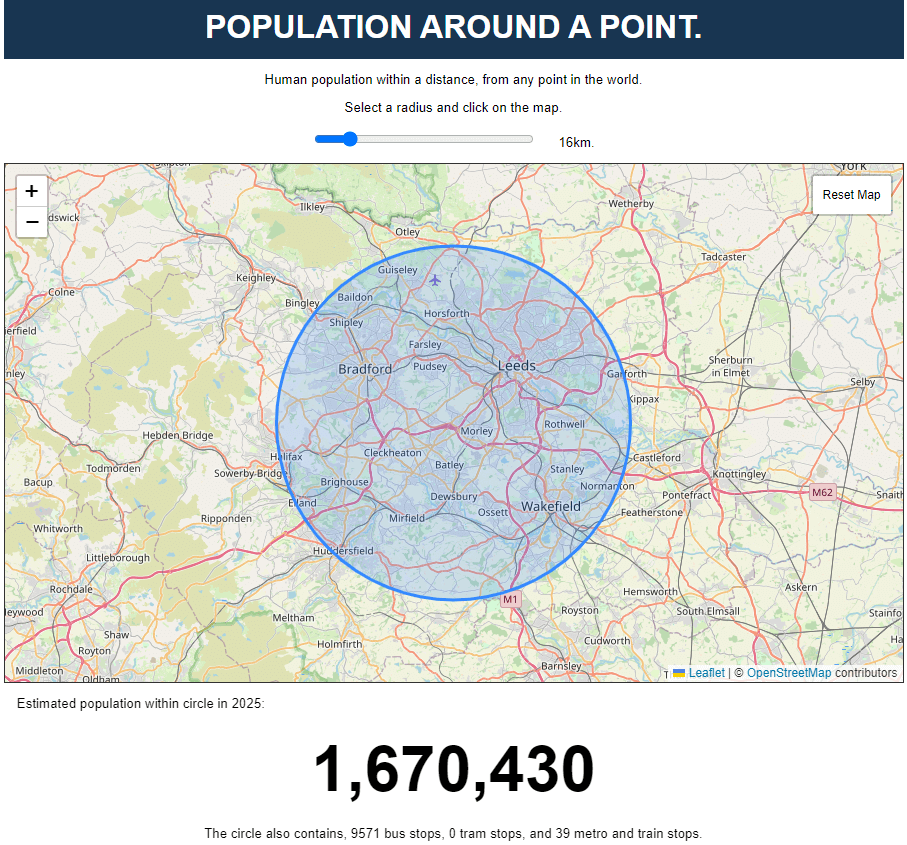

For example, he points out results from his own tool. This shows that, within a 10-mile circle of West Yorkshire which includes Leeds, Bradford and Wakefield, there are 10,000 bus stops for 1.7 million inhabitants.

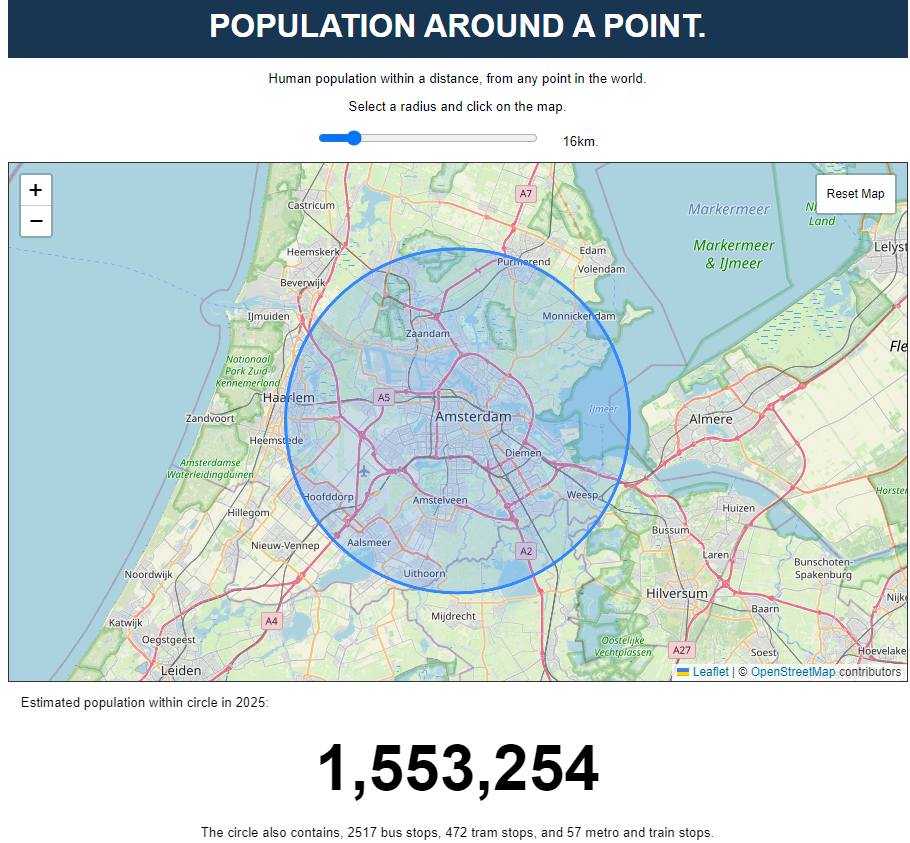

He compares that to Amsterdam, which over a 10-mile radius has only 2,500 bus stops serving a similar population.

We have double or even triple the number of bus stops of a Dutch city – Tom Forth

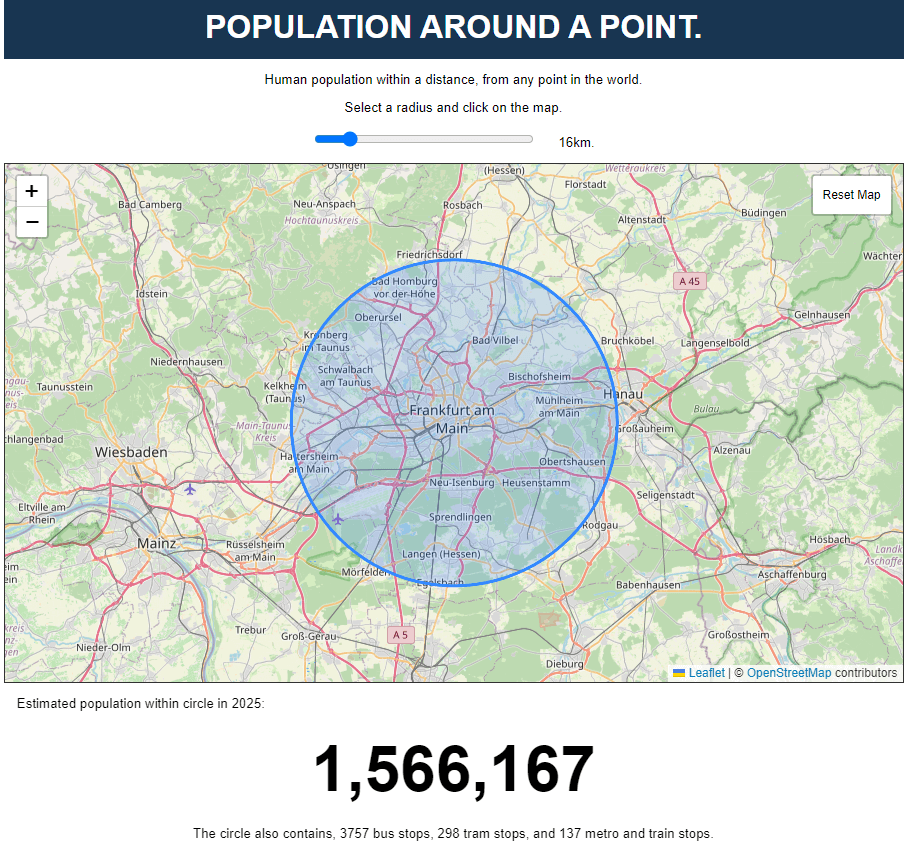

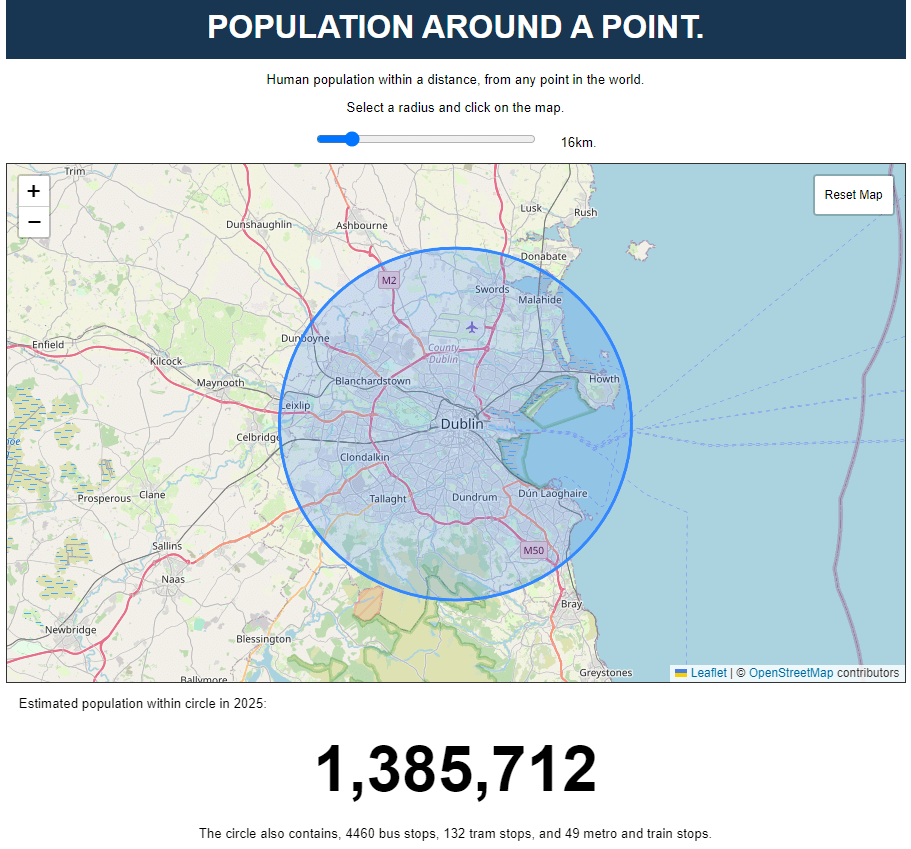

The same open data shows that around 1.6 million people within a 10-mile circle in Frankfurt have to make do with just 3,800 bus stops. For Dublin, it’s 4,500 bus stops for a similar population.

“As a rule of thumb, we have 50% more bus stops than a German city and we have double or even triple the number of bus stops of a Dutch city,” says Tom, who has worked with Transport for Greater Manchester, Leeds City Council, Bradford City Council, West Yorkshire Combined Authority, and the Department for Transport.

Success in Birmingham

The bus stop removal scheme in Birmingham was based on calculations that each stop added 35 seconds to the journey and that many of them were rarely used.

However, as one might imagine, the decision was not without negative feedback and petitions, with complaints about the elderly and those with a disability having to walk further.

Tom admits that the approach is a “trade off”. He adds: “If you remove bus stops, maybe half a percent or 0.1% of your potential customers are going to be unable to use the bus.

“You’ve got to be honest about it. Do you want to make the bus journey better for 99% of people at the cost of 1% of people?

“We have to make a moral judgment around that, especially around elderly and disabled people.

“We’ve tended in Britain to prioritise inclusivity and, probably, in a country like the Netherlands, they’ve chosen to prioritise the best journey for the highest number of people.”

However, the trial was deemed to be a success, with TfWM reporting an increase in 106,000 journeys over the six-month trial, which led to most of the stops being permanently deleted.

You’ve got to be honest about it. Do you want to make the bus journey better for 99% of people at the cost of 1% of people? – Tom Forth

A spokesperson for National Express West Midlands, told routeone last month: “We are focused on every opportunity to improve service for customers through shorter waiting times, faster journeys and a more efficient network.

“We saw an initial benefit on the services with fewer stops until the pandemic affected travel patterns and the benefit lessened.

“We track the impact of waiting and journey times against passenger numbers and, on a typical urban route in the West Midlands, a reduction of one minute in waiting times results in a 3-5% patronage increase, whilst a one-minute reduction in journey times achieves a 2-3% growth in patronage.

“We use advanced technology to continually analyse the data on stops, waiting and journeys to ensure our operations run efficiently.”

UK and global trends

Guidance from the Chartered Institution of Highways and Transportation in 2018 for planners of urban developments notes that bus stops will generally be 200-400m apart, with Transport for London and Stagecoach in 2017 recommending spacing of 300-400m and 280-320m respectively.

American transport consultant Jarrett Walker added on a recent trip to the UK that he had not observed bus stop distancing being a particular problem.

However, the founder of Jarrett Walker and Associates and author of the book Human Transit: How Clearer Thinking about Public Transit Can Enrich Our Communities and Our Lives adds: “Bus stops do affect running time and reliability.

“And we always want people to gather at the fewest possible bus stops so we make the fewest possible stops.

“I’m generally supportive of the prevailing European practice of having buses stop somewhere in the range of 400-600m, generally wider in areas of very high demand, which tend also to be areas of good walkability.

“The walkability of the neighbourhood is an important factor. If you have in a highly walkable inner-city fabric, you shouldn’t need to stop more than every 400m and, in many continental examples, you’ll find spacing up to 600m.”

Routes and franchising

Tom adds: “In addition to getting rid of some bus stops, I think that local authorities could also get rid of quite a lot of bus routes.

“We’ve got a very complicated bus route system in West Yorkshire and, when you’ve got different operators competing around different routes, they’ll often add more and more routes and make it more and more complex.

“Sometimes you need to take the brave decision and get rid of quite a lot and I think that will also happen with franchising pretty well.”

Tom’s work with local authorities has helped advise proposals around franchising of bus services. His personal view is that franchising would work well for the bigger cities but perhaps not at all for the smaller ones or rural areas.

“If you look at somewhere like York, for example, which I know quite well, I don’t see how franchising would massively improve buses,” he says.

“But, if you look at somewhere like West Yorkshire, effectively the franchising boost is that, if you’re ever going to have more than a very small fraction of your public transport users switch between different modes, like rail to bus, bus to tram, tram to underground, I’ve not seen example of that working without franchising.”

Multi-modal integration and simplification of ticketing systems would be one benefit of the trend towards reregulation that is being seen under a new Labour government, he points out.

Arguing for another, he adds: “If there’s congestion and a bus is slow in it, what does it cost the local authority? Nothing really. It costs the private operator.

“Under franchising, suddenly you’ll have a situation where congestion on the roads is costing the combined authority money because they’ll have to pay more for the franchise rights. So it aligns the incentives really well.

“My hope is that, if combined authorities see it’s costing them to have congestion, we will see an improvement in bus lanes and bus lane enforcement.”

Output from tomforth.co.uk/circlepopulations which compares, for selected conurbations, the number of bus stops within a 10-mile radius and covering a population of around 1.6 million inhabitants. © OpenStreetMap contributors

Tom Forth is Head of Data at the not-for-profit, independent organisation Open Innovations in Leeds and has a particular interest in public transport.