As Graham Vidler sets out in his column this month, the Confederation of Passenger Transport (CPT) will be lobbying the new government over the coming weeks on the sensible “asks” in CPT’s coach and bus manifestos.

Unlike times past, bus had reasonable visibility in the general election campaign, partly due to some exposure it received during mayoralty elections in the spring.

That said, Labour’s manifesto pledges also meant that, whenever buses came up, the debate tended to focus on issues around control, such as franchising and municipalisation, and to a lesser extent on funding.

Coach did not enjoy a high profile as an election issue, though CPT’s efforts helped it remain in the news in reference to the proposed Entry/Exit System, parking issues in certain constituencies, and the steady acquisition of CPT Coach Friendly credentials by a growing band of forward-thinking destinations and authorities that see the value of a partnership approach to improving access and facilities for coach.

But what about key policy items which didn’t receive an airing? Almost anything “net-zero” saw arguments about how progress towards this goal would be funded used as a stick to beat the other side.

We heard too little about how efficiently coach and bus can help cut congestion, improve air quality and achieve essential climate targets

With the exception of a report published by the climate charity Possible (calling for significant expansion of the express coach network), we heard too little about how efficiently coach and bus can help cut congestion, improve air quality and achieve essential climate targets.

It’s also a concern that a “war on the motorist” narrative employed in certain quarters during the election eroded a hard-won consensus around the importance of coach and bus for cutting the number of journeys made by car and freeing the road space these take up.

It is worrying, too, then that bus speeds and bus priority measures — each so important for enticing more people to abandon cars and catch a coach or bus — were ignored, especially given how effective action on these challenges will be crucial for any success in those areas already pursuing (or pledging to implement) a franchised model for bus service delivery.

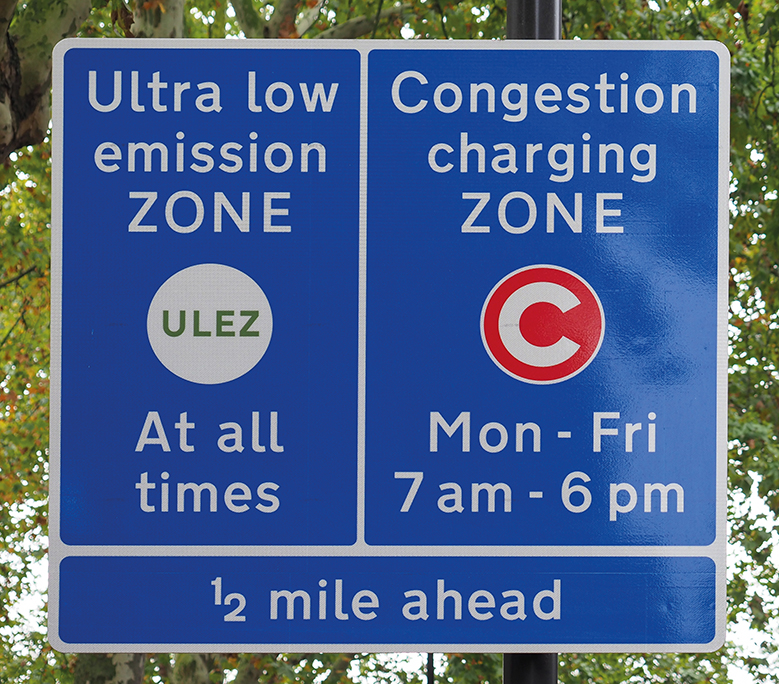

Another serious “elephant on the Tarmac” — road pricing and congestion charging — was also curiously absent from most parts of the general election debate.

Though weaponised in a few constituencies, and widely seen as politically toxic, I will risk suggesting this has not always been so.

A pressing need to reform Vehicle Excise Duty and find a more equitable way to tax future road usage also means the new government will — sooner rather than later — have to bring forward proposals in this area.

Research carried out for CPT has shown that an effective congestion charge applied comprehensively to all UK urban local authorities would lead to 250 million fewer car journeys every year.

As well as securing more road space for bus priority, equitable and effective road pricing would support the delivery of the new government’s aspirations to improve social inclusion and access to education or employment.

The discussion around this will be vivid because available technology means measures can be both specific and highly targeted.

For example, it could be by day, time of day or place, or by types and even models of vehicle (such as coach, bus or SUVs) or fuel type (EV, hybrid, hydrogen or diesel).

There is even scope to consider quotas, such as each person or vehicle receiving a specific permitted mileage at each of several escalating levels of price.

However, by far the most predictable facet of this debate is the bald fact that, to be effective, any form of road user charging must encourage people to think twice about taking the car when public transport offers a more affordable, frequent and reliable option.